|

Six Sigma quality, the closest thing to

a management fad to have surfaced since the dotcom bust, has passed

its peak, a leading financial newspaper argued several weeks ago.

If Six Sigma continues to follow past patterns, the next stage will

be disenchantment, as companies find that the technique often achieves

less than expected.

Whether this statement is true or false

is not a debate here. More interesting is the assumption behind the

statement: that management trends and quality concepts come and go,

and no matter which ones are in at the moment, they all must serve a

criterionprofitability.

Any quality assurance system must align with this credo.

Lets put the knotty statistics,

procedures, theories, charts, and graphics aside, and instead look at

the core of a quality system. To start with, from a cost-management

point of view, the quality assurance function is a cost center, not a

profit center. To serve the corporate core ideology of profitability,

a pragmatic quality assurance system has to be built and maintained

with the lowest cost possible and accomplish two basic functions:

Monitor

performancedistinguish the good and the bad and report deviations.

Drive continuous

improvementprovide information on current performance and root

causes to guide continuous improvement initiatives.

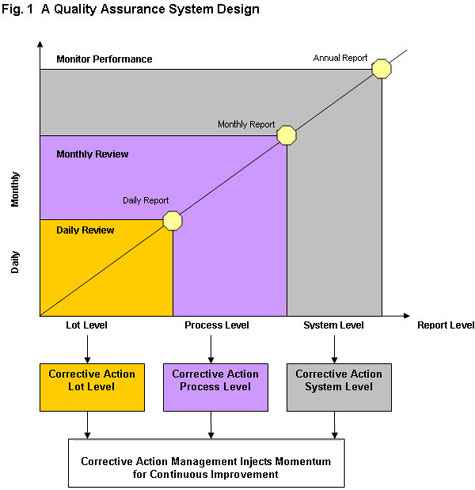

Figure

1 illustrates a design of such a quality assurance system. To monitor

operational performance effectively throughout the organization, the

performance review is divided into three levels based on

organizational hierarchies and time frames. To inject momentum into

continuous improvement activities, each review should define the

weakest links and issue corrective action requests to resolve weakest

links. Figure

1 illustrates a design of such a quality assurance system. To monitor

operational performance effectively throughout the organization, the

performance review is divided into three levels based on

organizational hierarchies and time frames. To inject momentum into

continuous improvement activities, each review should define the

weakest links and issue corrective action requests to resolve weakest

links.

In this design, each of the three levels

of performance review naturally implies a focus for corrective action:

First leveldaily

review of work order/lot performance. In Japan, this is a morning

routine. In five-minute pre-production meetings, supervisors highlight

the major problems of the previous day, and operators discuss how to

prevent them in the future. Focus of corrective actions: improvement

of operators routine activities.

Second levelmonthly

review of summarized process performance. The typical application is a

monthly operational performance review involving a cross-functional

team of managers/directors. Focus of corrective actions: process

improvements.

Third levelannual

or quarterly review of system performance. Best practice is the

annual/quarterly performance review or a scheduled failure modes and

effects analysis (FMEA) review. Focus of corrective actions:

improvement of system efficiency based on long-term performance and

lessons from past failures. Implementing such a design sounds

undemanding; however, the real challenge is to execute the theories

with a reasonable cost. Most of the time, management fashions fade

away because of digressions, high implementation and maintenance

costs, and less than expected outcomes.

Lately, I came across a service-sector

quality system in need of improvement. To expedite the organizations

order-handling process and improve accuracy, the quality manager

initiated a project to collect data on total time spent versus

standard time. Periodically, the total lost-time was calculated as an

indicator of process performance. Can you see what is going wrong

here?

Lets put the question in another form,

and then we will be able to see the problem more clearly: Is the

total lost-time adequate to drive and direct improvements on reducing

processing time and improving order accuracy? Obviously, the answer

is no! More process information is needed to identify the root causes

in order to make improvements. This is a classic example of system

implementation wandering from the core of a quality system, which is

to drive improvement.

So let me reiterate: to preserve the

coredriving improvementthe monitoring system shall focus on

defects and root causes rather than the outcome of a process.

A simple and easy way to maintain optimal

implementation and maintenance cost is to employ a good software

package to manage the whole system. However, selecting the wrong

software could allow minor problems to turn into disasters, increasing

your costs even more.

Here are some practical rules for

selecting a good software package:

-

Above all, the package should be a

database instead of a single-purpose application. Many SPC packages

available on the market are single-purpose applications; they

primarily focus on statistical calculations, and they are not

capable of easing the everyday data-crunching tasks of data

retaining and summarizing and performance reporting and charting.

-

The software package should have the

capability to store and retrieve data such as process input, defect

quantities, defect descriptions, cycle time, etc.

-

The software package should have the

capability to summarize data automatically and generate performance

reports on the three performance review levels mentioned above.

-

The software package should have

corrective action issuing and management capability.

-

Incorporating Quality Knowledge Base

capability will enable quality professionals to learn from past

failures.

If Six Sigma is to

have a lifespan that outlasts management fads and quality trends, it

must continue to serve the ultimate purpose of profitability. This

means driving improvement by dealing with root causes. Granted, Six

Sigma does perhaps start with a stronger focus on process and root

cause analysis than many previous initiatives. Nevertheless, some

management of the overall implementationwhether by using a software

package or another means of monitoring and driving improvementis the

best way of ensuring that it stays true to its focus.

Author: Logan Luo

QIT Consulting, Inc.

Copyright C 2003 ASQ

Six Sigma Forum. All rights reserved.

|